Aristotle’s Great Souled Man

I make notes here on Aristotle’s description of the Great Souled Man.

All of the sources for this post come from Roger Crisp and his article “Aristotle on Greatness of Soul,” which can be found

here. Source text is in

blue italics.

(1) Risk and danger (IV.3.1124b6–9):

The great-souled person, because he does not value anything highly, does not enjoy danger. He will avoid trivial dangers, but will face great ones, and, again because of his attitude to goods, will be unsparing even of his own life.

The Magnanimous Man faces great dangers. Trivial dangers are below him. He even faces deadly dangers.

(2) Giving and receiving benefits (IV.3.1124b9–18):

The great-souled person is inclined to help others readily, but he is ashamed to be a beneficiary, since it is a sign of inferiority. If he is benefited, he will repay with interest, to ensure that his benefactor becomes a beneficiary. He will remember with pleasure benefits he has conferred, but will forget those he has received and feel pain on being reminded of them.

The Magnanimous Man tends to be prepared to help others. Getting help shames him, since this signals inferiority in reference to the benefactor, so he will repay the debt with interest. Memories of giving bring him pleasure, but he will forget received gifts because the memory will bring him pain.

(3) Attitude to others (IV.3.1124b18–23):

The great-souled person will be proud [megas] in his behavior toward people of distinction, but unassuming toward others. For superiority over the former is difficult and impressive, while over the latter it is easy and vulgar.

He carries himself with pride and honor among honorable men, but becomes unassuming when among common people. Effort is required to carry himself among the honorable - a worthy task, but impressing the common people is easy, and thus, not a worthy task.

(4) Level of activity (IV.3.1124b23–6):

The great-souled person avoids things usually honored, and activities in which others excel. He is slow to act except where there is great honor at stake, and he is inclined to perform only a few actions, though great and renowned ones.

He preserves his effort for only those things involving great honor. He avoids the usual honor of things thought of as excellent.

(5) Openness (IV.3.1124b26–31):

Because the great-souled person cares little for what people think, he is open in his likes and dislikes. And because he is inclined to look down on people, he speaks and acts openly, except when using irony for the masses.

He speaks his mind about likes and dislikes among the honorable people, since he cares little for what others think. He will tend to look down on others. When speaking to the common man, he will speak with irony.

(6) Independence and self-sufficiency (IV.3.1124b31–1125a16):

The great-souled person will not depend on another, unless he is a friend, because to do so would be servile. Because nothing matters to him, he is not inclined toward admiration, resentment, gossip, praise of others, or complaining. His possessions are noble rather than useful, because this is consistent with self-sufficiency. Again because nothing matters to him, he will not be rushed: His movements are slow, his voice is deep, and his speech is measured.

He does not depend on others, which would make him a servant. He only depends on friends. He does not much admire or complain. The things he has are symbolic, and not necessarily useful. He is not in a hurry. He moves slowly. He has a deep voice, and he speaks with efficiency.

///

Commentary

This description seems like a fragment. I am not sure how many ancient texts survived these two millennia, but this feels like a sketch or a draft. Aristotle, in his greatness, must have written much more on this subject. Some believe that we have only one-third of his original works.

Depth of feeling is not one of the traits. Today, after the Romantic Era from 1820 to 1900, we have a tradition of honoring deep feeling. Perhaps the ancients thought that this was self-indulgent.

Spirituality is not apparent here. A man of rituals, with meditation and contemplation, seems not to be one of this type. Can a great priest be a Great Souled man? It is perhaps not conceivable with this description.

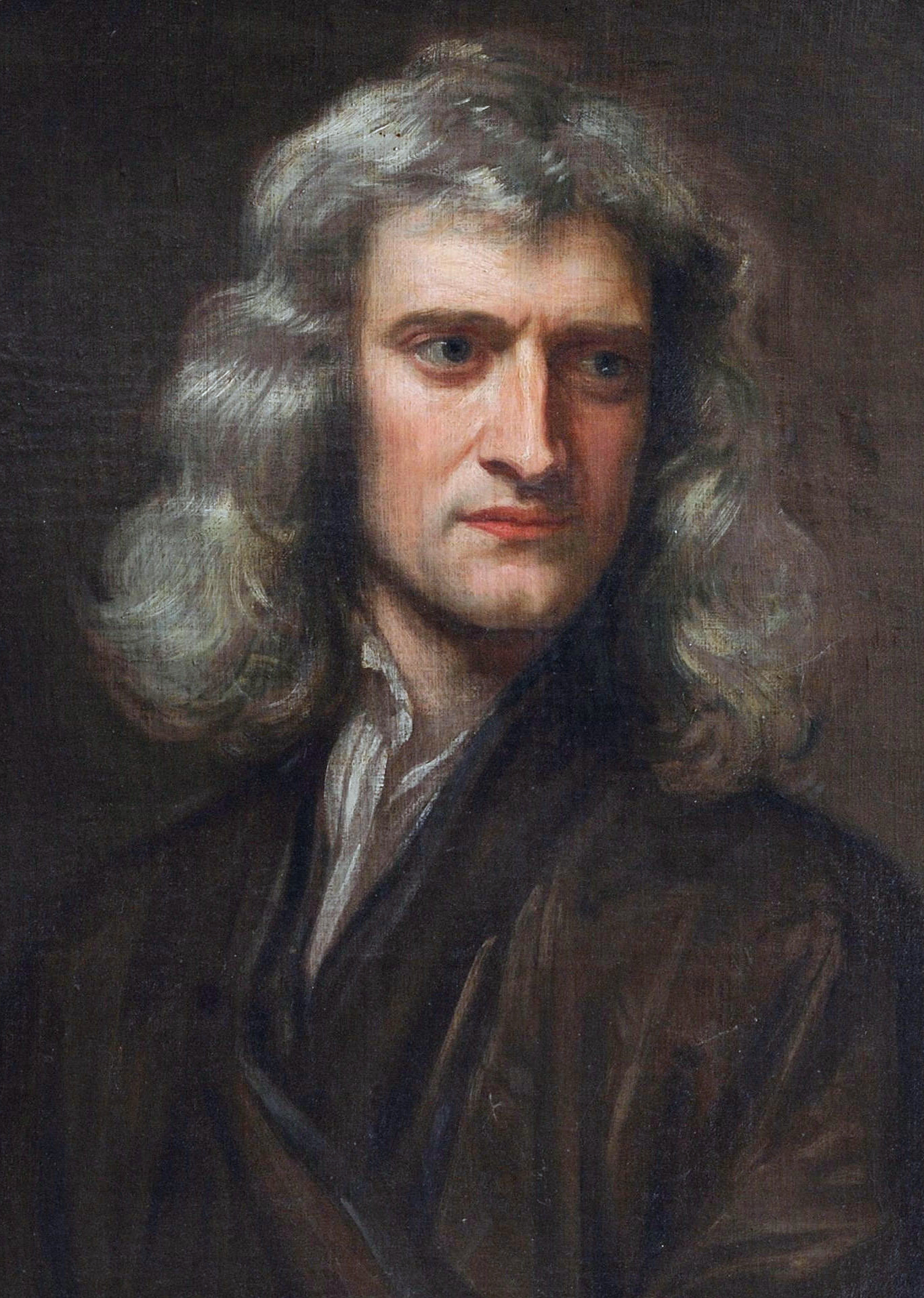

Figures that come to mind with this description are Frederick the Great, Napoleon, George Washington, Wellington, Arnold Schwarzenegger (no joke, I read his biography several times), George Patton, Louis XIV, among others. Jacques Barzun may also be a candidate.

These people tend not to be likable, except to their friends, with the exception of Schwarzenegger, which may turn many off, although he is definitely a Great Man, with no exaggeration on my part.

So, is Aristotle describing a great general? A soldier? He is definitely not describing a priest. For every society, the two leaders that emerge are Priest and Warrior. This description fits more closely to the warrior type.

///

Freddy Martini